Giardia lamblia (duodenalis, intestinalis) (Pathogen)

Organism:

This organism belongs to the flagellates, is a true pathogen, and causes giardiasis. Both the trophozoite (usual size, 10-20 µm long and 5-15 µm wide) and cyst forms (usual size, 11-14 µm long and 7-10 µm wide) can be found in clinical specimens.

Life Cycle:

Intestine (duodenum, occasionally gallbladder and rarely bronchoalveolar lavage fluid), organisms passed in feces

Acquired:

Fecal-oral transmission via cyst form; contaminated food and water. Various studies have published data suggesting that zoonotic transmission between humans and animals is, at times, more likely or less likely to occur.

Epidemiology:

Worldwide, primarily human-to-human transmission

Clinical Features:

Intestinal: Diarrhea, epigastric pain, flatulence, increased fat and mucus in stool, gallbladder colic and jaundice. The incubation time for giardiasis ranges from approximately 12 to 20 days. Because the acute stage usually lasts only a few days, giardiasis may not be recognized as the cause but may mimic acute viral enteritis, bacillary dysentery, bacterial or other food poisonings, acute intestinal amebiasis, or "traveler's diarrhea" (toxigenic Escherichia coli). However, the type of diarrhea plus the lack of blood, mucus, and cellular exudate is consistent with giardiasis.

The acute phase is often followed by a subacute or chronic phase. Symptoms in these patients include recurrent, brief episodes of loose, foul‑smelling stools; there may be increased distention and foul flatus. Between passing the mushy stools, the patient may have normal stools or may be constipated. Abdominal discomfort continues to include marked distention and belching with a rotten‑egg taste. Chronic disease must be differentiated from amebiasis; disease caused by other intestinal parasites such as Dientamoeba fragilis, Cryptosporidium spp., Cyclospora cayetanensis, Isospora belli, Strongyloides stercoralis; and inflammatory bowel disease and irritable colon. On the basis of symptoms such as upper intestinal discomfort, heartburn, and belching, giardiasis must be differentiated from duodenal ulcer, hiatal hernia, and gallbladder and pancreatic disease.

Clinical Specimen:

Intestinal: Stool, duodenal aspirates, EnteroTest capsule, biopsy

Extraintestinal: Fluids

Laboratory Diagnosis*:

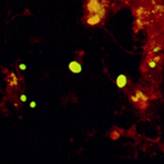

Intestinal: Ova and Parasite examination (concentration, permanent stained smear); fecal immunoassay to detect Giardia (antigen and/or actual organism using FA immunoassay); two fecal immunoassays are required prior to reporting a negative antigen (due to shedding patterns).

Extraintestinal: Trichrome, PAS stains, routine histology (H&E stain)

Organism Description:

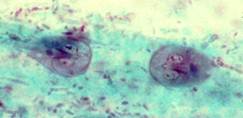

Trophozoite: Teardrop shaped from the front, curved portion of a spoon from the side; two nuclei, curved median bodies, linear axonemes

Cyst: Round to oval, will contain 4 nuclei and more median bodies and axonemes; cysts are very three-dimensional; they may also appear to be shrunk within the cyst membrane.

Laboratory Report:

Giardia lamblia (indicate trophozoites and/or cysts)

Treatment: Garcia, L.S. 2007. Diagnostic Medical Parasitology, 5th ed., ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

In the absence of a parasitologic diagnosis, the treatment of suspected giardiasis is a common question with no clear‑cut answer. The approach depends on the alternatives and the degree of suspicion of giardiasis, both of which will vary among patients and physicians. However, it is not recommended that treatment be given without a good parasitologic workup, particularly since relief of symptoms does not allow a retrospective diagnosis of giardiasis; the most commonly used drug, metronidazole, targets other organisms besides G. lamblia.

Another question involves treatment of asymptomatic patients. Generally, it is recommended that all cases of proven giardiasis be treated because the infection may cause subclinical malabsorption, symptoms are often periodic and may appear later, and a carrier is a potential source of infection for others. Certainly, in areas of the world where infection rates, as well as the prospect of reinfection, are extremely high, the benefit‑per‑cost ratio would also have to be examined.

Control:

Improved hygiene, adequate disposal of fecal waste, adequate washing of contaminated fruits and vegetables. Most experts agree that the single most effective practice that prevents the spread of infection in the child care setting is thorough handwashing by the children, staff, and visitors. Rubbing the hands together under running water is the most important part of washing away infectious organisms. Premoistened towelettes or wipes and waterless hand cleaners should not be used as a substitute for washing hands with soap and running water. These guidelines are not limited to giardiasis but include all potentially infectious organisms.

Because of the potential for wild animal and possibly domestic animal reservoir hosts, measures in addition to personal hygiene and improved sanitary measures have to be considered. Iodine has been recommended as an effective disinfectant for drinking water, but it must be used according to directions. Filtration systems have also been recommended, although they have certain drawbacks, such as clogging.

Comments:

Even with multiple stools, the infection may be missed; this is also true when using fecal immunoassays; more than 1 specimen may have to be tested (FA, EIA, lateral flow cartridge).