Fasciola hepatica (Pathogen – Liver Trematodes)

Organism:

Fascioliasis (sheep liver fluke disease) is primarily a zoonotic disease that produces liver infections with adult flukes. Over 2.4 million people are infected with this parasite worldwide. F. hepatica was the first trematode to be described and the first for which the entire life cycle was defined; it is interesting that approximately 500 years passed between the description of the parasite and clarification of the life cycle. The first recorded information on F. hepatica infections was provided by de Brie in 1379, when he described the effects of certain types of water plants on sheep that had eaten them. The complete life cycle was established by the investigations of Leuckart and Thomas in 1883, independently of one another. The most common definitive hosts are sheep; however, other herbivores such as goats, cattle, horses, camels, hogs, vicuna, rabbits, and deer are often infected as well. In sheep, the migratory phase produces such extensive liver parenchyma damage that the disease is known as liver rot. Although the disease has a cosmopolitan distribution, only a single case of autochthonous infection in a human in the United States has been reported.

|

|

|

|

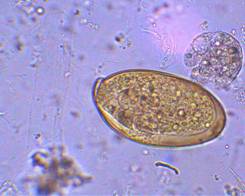

| Eggs (operculated) | X-section in liver |

|

|

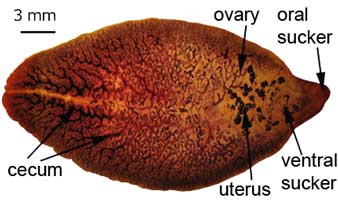

Adult worms

Life Cycle:

Adult worms, which may live for many years in the bile ducts, produce eggs that are carried by the bile fluid into the intestinal lumen and passed into the environment with the feces. The eggs are unembryonated, operculated, large, ovoid, and brownish yellow and measure 130 to 150 μm by 63 to 90 μm. The miracidium develops within 1 to 2 weeks in water from 22 to 26°C and escapes from the egg to infect the snail intermediate host, Lymnaea sp. These snails are amphibious. Within 4 to 7 weeks, cercariae are liberated from the snail after the production of a sporocyst generation and two or three redia generations. Cercariae encyst on water vegetation, e.g., watercress. Humans are infected by ingestion of uncooked aquatic vegetation on which metacercariae are encysted. Metacercariae excyst in the duodenum and migrate through the intestinal wall into the peritoneal cavity. The larvae enter the liver by penetrating the capsule (Glisson's capsule) and wander through the liver parenchyma for up to 9 weeks. The larvae finally enter the bile ducts, where they mature and produce eggs, which are passed out in the feces. The adult worms can attain a length of 30 mm and a width of about 13 mm and can live for more than 10 years.

Acquired:

Humans are infected by ingestion of uncooked aquatic vegetation on which metacercariae are encysted.

Epidemiology:

Fascioliasis is a cosmopolitan disease that is found where there is close association of livestock, humans, and snails. The largest numbers of infections have been reported from Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, France, Iran, Peru, and Portugal. Although animal fascioliasis is endemic throughout the Americas, human infections are rare in most countries. Reservoir hosts include herbivores such as cattle, goats, and sheep. Animal fascioliasis is a major veterinary problem in Europe. The infection is contracted by the ingestion of metacercariae encysted on uncooked water plants, such as watercress. Watercress is the main source of infection; however, in many countries, wild watercress is touted as a healthy natural food. In many areas of the world, animal manure is used as the primary fertilizer for cultivation of watercress.

In surveying potential risk factors in the Northern Peruvian Altiplano, the principal exposure factor for F. hepatica infection was drinking alfalfa juice. Human fascioliasis in Peru should be suspected in patients from areas where livestock is raised who present with recurrent episodes of jaundice and who have a history of alfalfa juice or aquatic plant ingestion, or who have eosinophilia.

Clinical Features:

The incubation period for this infection can range from a few days to a few months. The patient's symptoms will reflect the phase of the infection, as well as the number of parasites present in the host. In the acute phase, symptoms may be present over a period of weeks to months. Metacercarial larvae do not produce significant pathologic damage until they begin to migrate through the liver parenchyma. The amount of damage depends on the worm burden of the host. Linear lesions of 1 cm or greater can be found. Hyperplasia of the bile ducts occurs, possibly as a result of toxins produced by the larvae. Symptoms associated with this migratory phase have included fever, epigastric and right upper quadrant pain, intestinal complaints, and urticaria, although other patients remain asymptomatic. Asymptomatic infections appear to be more common in Peru. Other symptoms include loss of appetite, flatulence, nausea, diarrhea, and a nonproductive cough. Patients may also have hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, chest signs, and jaundice. Leukocytosis, eosinophilia, and mild to moderate anemia are found in many patients. Levels of IgG, IgM, and IgE in serum are usually elevated.

In the more chronic phases of the disease, the patient generally has few to no symptoms once the flukes have lodged in the biliary passages. However, there may be some epigastric and right upper quadrant pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, hepatomegaly, and jaundice. If the flukes are found in the extrahepatic biliary ducts, symptoms may mimic those seen in cholelithiasis. In the chronic phase, there tends to be some liver function abnormalities, as well as eosinophilia. Larvae may be found in ectopic foci after penetrating the peritoneal cavity. Worms in human infections have been discovered in many areas of the body other than the liver. Other body sites include the intestinal wall, lungs, heart, brain, and skin. Symptoms mimic those seen with visceral larva migrans and include vague abdominal pain. Unfortunately, surgery may be required to determine the exact cause of the symptoms.

Once the worms have established themselves in the bile ducts and matured, they cause considerable damage from mechanical irritation and metabolic by‑products as well as obstruction. The degree of pathologic change depends on the number of flukes penetrating the liver. The infection produces hyperplasia of the biliary epithelium and fibrosis of the ducts with portal or total biliary obstruction. The gallbladder undergoes similar pathologic changes and may even harbor adult worms. Adult worms may reinvade the liver parenchyma, producing abscesses.

Symptoms and signs of infection during the late stages after egg production has begun are those associated with biliary obstruction and cholangitis. Acute epigastric pain, fever, pruritus, jaundice, hepatomegaly, and eosinophilia are common.

In areas of endemicity where uncooked goat and sheep livers may be eaten, such as Lebanon, adult worms may attach to the pharyngeal mucosa, causing suffocation (halzoun syndrome). This condition is temporary, although it may produce considerable discomfort. The adult worms may lodge on the pharyngeal mucosa causing edema and congestion of the soft palate, pharynx, larynx, nasal fossae, and eustachian tube. The symptoms include dyspnea, dysphagia, deafness, and occasionally suffocation. It has also been suggested that a number of these cases may be caused by infection with larval linguatulids, rather than adult worms of F. hepatica.

Clinical Specimen:

Stool: Confirmation of the infection depends on finding the operculated eggs in a routine stool examination; multiple stool examination may be required to find the eggs.

Laboratory Diagnosis:

Stool: The routine sedimentation concentration is recommended. Since the eggs are operculated they cannot be recovered from the zinc sulfate flotation method. The eggs of F. hepatica, Fasciolopsis buski, E. ilocanum, and G. hominis are similar in size and shape. Differentiation may be difficult without a patient history. Patients may be symptomatic during the first weeks of infection, but no eggs will be found in the stool until the worms mature, which takes 8 weeks. Multiple stool examinations may be needed to detect light infections.

Serum: Serologic diagnosis with F. hepatica excretion‑secretion antigens has been successfully used in areas of endemicity to detect patient antibodies. This approach includes ELISA, counterelectrophoresis, and enzyme‑linked immunoelectrotransfer blots. Serologic tests can be used to monitor treated patients to ensure successful therapy. Serologic cross‑reactions have been noted in patients infected with schistosomiasis. Serologic tests are the test of choice for the diagnosis of acute and chronic fascioliasis when few eggs can be found in the stool or when large populations are to be screened.

.

Organism Description:

Egg: The eggs are unembryonated, operculated, large, ovoid, and brownish yellow and measure 130 to 150 μm by 63 to 90 μm. The eggs of F. hepatica, Fasciolopsis buski, E. ilocanum, and G. hominis are similar in size and shape. Differentiation may be difficult without a patient history. Patients may be symptomatic during the first weeks of infection, but no eggs will be found in the stool until the worms mature, which takes 8 weeks. Multiple stool examinations may be needed to detect light infections.

Laboratory Report:

Fasciola typeeggs recovered

Treatment:

Although praziquantel is sometimes effective at a dose of 25 mg/kg taken after each meal for 2 days, it does not appear to be effective in treating patients in Egypt. Treatment with biothionol at 30 to 50 mg/kg on alternate days for 10 to 15 doses is recommended. Triclabendazole at 10 mg/kg as a single dose is also recommended, but this dose may not be as easily obtained. If a single dose has failed, the use of 20 mg/kg triclabendazole is recommended. The drug is given orally in single or multiple doses and has few side effects. It acts by inhibiting protein synthesis in F. hepatica and will probably become the drug of choice; however, it is not currently available in the United States unless possibly available through a compounding pharmacy.

Garcia, L.S. 2007. Diagnostic Medical Parasitology, 5th ed., ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

Control:

Prevention may be accomplished by public health education in areas where infections are endemic, stressing the dangers of eating watercress grown in the wild where animals and snails are abundant. Other measures have included killing snails, treating infected animals, and draining pasture lands.