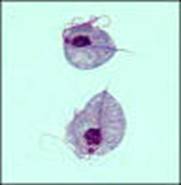

Trichomonas vaginalis (Pathogen)

Organism:

This organism belongs to the flagellates, is a pathogen, and causes disease. The trophozoite (usual size, 7-23 µm long and 5-15 µm wide) can be found in clinical specimens such as urine, urethral discharge, and vaginal smears.

|

|

|

Life Cycle:

Urinary-genital system; no known cyst form.

Acquired:

Although the exact mode of transmission is not known, it is assumed to be by sexual transmission or rarely contaminated towels, underpants, etc. Humans are the only natural host for T. vaginalis, and normal body sites for these organisms include the vagina and prostate. Apparently, the organisms feed on the mucosal surface of the vagina, where bacteria and leukocytes are found. The preferred pH for good growth in females is slightly alkaline or acidic (6.0 to 6.3 optimal), not the normal pH of the healthy vagina.

Epidemiology:

Worldwide. It is estimated that 5 million women and 1 million men in the United States have trichomoniasis, with an annual incidence estimated to be 7.4 million new cases. The annual incidence of trichomoniasis worldwide is estimated to be more than 170 million cases, which does not include the number of asymptomatic cases that are not treated. In North America, more than eight million new cases are reported yearly, with an estimated rate of asymptomatic cases being as high as 50%. Trichomoniasis is now the primary nonviral sexually transmitted disease worldwide. Infection with T. vaginalis has major health consequences for women, including complications in pregnancy, association with cervical cancer, and predisposition to HIV infection.

Clinical Features:

T. vaginalis is site specific and usually cannot survive outside the urogenital system. Although the incubation period is not well-defined, in vitro studies provide a range of 4 to 28 days. After introduction, proliferation begins, with resulting inflammation and large numbers of trophozoites in the tissues and the secretions. As the infection becomes more chronic, the purulent discharge diminishes, with a decrease in the number of organisms. The onset of symptoms such as vaginal or vulval pruritus and discharge is often sudden and occurs during or after menstruation as a result of the increased vaginal acidity. In acute infections, diffuse vulvitis is seen and is due to copious leukorrhea. The discharge is frothy, yellow or green, and mucopurulent; however, only about 10 to 12% of women exhibit this frothy discharge. Small punctate hemorrhagic spots can be seen on the vaginal and cervical mucosa; this has been called a "strawberry appearance" and is seen in about 2% of patients. In general, symptoms include vaginal discharge (42%), odor (50%), and edema or erythema (22 to 37%). Other complaints include dysuria and lower abdominal pain.

In chronic infections, symptoms may be very mild with pruritus and some pain during sexual intercourse, while the vaginal secretion may be scanty and mixed with mucus. Individuals with these symptoms are the major source of transmission. From 25 to 50% of infected women may be asymptomatic and have a normal vaginal pH of 3.8 to 4.2 and normal vaginal flora. Although there is a carrier form, about 50% of these women will develop clinical symptoms during the following six months.

T. vaginalis may also cause neonatal pneumonia.

Clinical Specimen:

Urogenital System: Vaginal and urethral discharges, prostatic secretions. Since the morphology of nonpathogenic P. hominis from stool samples is very similar to that of pathogenic T. vaginalis, it is important to ensure that the specimen is not contaminated with fecal material.

Laboratory Diagnosis:

Urogenital System: Diagnosis is based on the recovery of the organisms from the appropriate clinical specimen. Wet mounts, stained smears, culture, and antigen detection are available. Recombinant DNA techniques are becoming more widely available.

Organism Description:

Trophozoite: The trophozoite is pear-shaped, has a jerky, rapid motility; the undulating membrane extends half the length of the trophozoite with no free posterior flagellum; the axostyle is seen to protrude through the bottom of the organism

Laboratory Report:

Trichomonas vaginalis (indicate trophozoites)

Treatment:

Garcia, L.S. 2007. Diagnostic Medical Parasitology, 5th ed., ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

Control:

Infection is acquired primarily through sexual intercourse, hence the need to diagnose and treat asymptomatic males. The organism can survive for some time in a moist environment such as damp towels and underclothes; however, this mode of transmission is thought to be very rare. Evidence continues to accumulate implicating T. vaginalis as a potential contributor to poor outcomes in both women and men. In women, this infection may play a role in development of cervical neoplasia, postoperative infections, and potential problems with pregnancy. It is also seen as a factor in atypical pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility. In men, trichomoniasis causes nongonoccocal urethritis and contributes to male infertility.

Comments:

As with many sexually transmitted diseases, infection with T. vaginalis does not produce long-term immunity. Although the antibody response to this organism is well documented, the antibodies provide only limited protection, and antibody titers disappear after therapy. Vaccine development has shown some promise; potential targets include a 100-k-Da protein that is immunogenic across a number of T. vaginalis isolates; and essential adherence molecules such as adhesins, mucinases, and cysteine proteinases. Although several vaccine trials were held during the 1960’s and the late 1970’s, subsequent studies led to doubts about the efficacy of the vaccines. However, a whole-cell T. foetus vaccine is now commercially available for cattle and provides protection, as well as accelerating eradication of infection.