Necator americanus, Ancylostoma duodenale (Pathogen – Intestinal Nematode)

Organism:

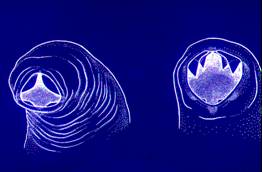

Necator americanus (New World Hookworm) and Ancylostoma duodenale (Old World Hookworm) belong to the nematodes, are pathogenic, and cause disease. These adult nematodes measure 7-13 mm (female) and 5 to 11 mm long (male). The adult worms are rarely recovered from the stool, since they are attached to the intestinal mucosa, feeding on blood obtained from the mucosal capillaries. It has been estimated that a single hookworm (Ancylostoma duodenale) ingests as much as 0.2 ml of blood per day, while N. americanus ingests approximately 0.05 ml.

|

|

|

|

| Adult Hookworm attached to mucosa | Necator (left), Ancylostoma (right) |

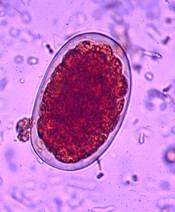

Hookworm egg | Hookworm egg containing larva |

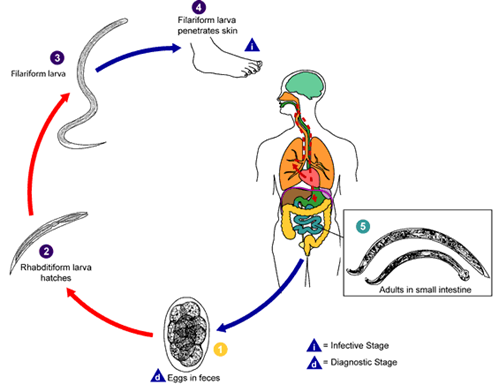

Hookworm life cycle

Life Cycle:

Human infection is acquired through skin penetration of infective larvae from the soil. The larvae migrate to the lungs, pass through the trachea and pharynx, enter the GI tract and attach to the intestinal mucosa. Hookworms can survive for several years, and eggs are passed in the stool (diagnostic stage). The total period from larval penetration to egg production is about 4-8 weeks.

Acquired:

Infection in humans is acquired through skin penetration of infective larvae (filariform larvae) from contaminated soil.

Epidemiology:

Worldwide it is estimated that there are 900 million infected individuals. Infection with hookworm is more common in warm, moist areas of the world. Worm burdens vary considerably; those individuals having few worms tend to be asymptomatic. Several factors influence hookworm prevalence: infection in the human population, defecation onto the soil, acceptable environmental conditions, and human contact with the infective larvae in soil. Environmental conditions include temperature, rainfall pattern, and the presence of open, sandy soil.

Clinical Features:

Initial symptoms after larval penetration of the skin often depend on the number of larvae involved. There may be minimal to severe pruritus and possible secondary infection if the lesions become vesicular and are opened by scratching. The development of vesicles from the erythematous papular rash is called ground itch. Any pneumonitis due to migrating larvae depends on the number of larvae present. These larvae do not cause the same level of sensitization seen with Ascaris or Strongyloides infection.

Symptoms from the intestinal phase of the infection are caused by (i) necrosis of the intestinal tissue within the adult worm mouth and (ii) blood loss by direct ingestion of blood by the worms and continued blood loss from the original attachment site, possibly as a result of anticoagulant secreted by the worm.

Patients with acute infections involving many worms may experience fatigue, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea with black to red stools (depending on the level of blood loss), weakness, and pallor. As in many other parasitic infections, heavy worm burdens in young children may have serious sequelae, including death. During this acute intestinal phase, there will be an increased peripheral eosinophilia. Eosinophilia is common, usually develops 25 to 35 days after exposure, and peaks about a month (N. americanus) to 2 months (A. duodenale) later.

In chronic infections, the main symptom is iron deficiency anemia (microcytic, hypochromic) with pallor, edema of the face and feet, listlessness, and hemoglobin levels of 5 g/dl or less. There may be cardiomegaly and both mental and physical retardation.

There is evidence for a protective role of helminth infection against asthma and malaria; however helminth infection may increase susceptibility for HIV/AIDS or tuberculosis. People with hookworm infection are also more likely to be infected with A. lumbricoides and T. trichiura, findings that can only partially be explained by overlapping endemic areas and potential exposure.

Clinical Specimen:

Stool: Definitive diagnosis of hookworm infection depends on demonstration of the eggs in stool, especially since the symptoms cannot be differentiated from malnutrition. The eggs are best seen in the direct smear or the concentration sediment but will be distorted on the permanent stained smear.

Laboratory Diagnosis:

Stool: The standard O&P examination is the recommended procedure for recovery and identification of Hookworm eggs in stool specimens, primarily from the wet preparation examination of the concentration sediment. Most infections can be easily diagnosed by finding these characteristic eggs in the stool.

Organism Description:

Egg: Eggs are normally passed in the stool in the unembryonated state (usually about an 8‑ to 32‑cell stage of development). There are typically a thin shell and clear space between the developing embryo and the shell. They are oval with broadly rounded ends and measure approximately 60 μm long by 40 μm wide.

Note. If the stool specimen is stored at room temperature (no preservative) for more than 24 h, the larvae will continue to mature and hatch. These larvae must be differentiated from Strongyloides larvae, since therapy is often different for the two infections.

Adult worm: The adult worms are rarely recovered from the stool, since they are attached to the wall of the intestine. The majority of cases are diagnosed on the presence of the typical eggs.

Laboratory Report:

Hookwormeggs present.

Treatment:

There are several effective therapeutic agents, including mebendazole, pyrantel pamoate, and albendazole, which are available in the United States.

Garcia, L.S. 2007. Diagnostic Medical Parasitology, 5th ed., ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

Control:

Sanitary disposal of feces is the primary means of infection control. This is sometimes difficult in poor rural communities where sanitary facilities are minimal or absent. An overall prevention approach also requires educational programs. The wearing of shoes and the use of soil sterilization have not proven to be practical.