Anisakiasis, (Anasakis, Pseudoterranova, Phocanema, Contracaecum) (Pathogen - Tissue Nematode)

Organism:

Anisakiasis (tissue nematodes) was first recognized and reported in the Netherlands. Since this infection was reported in Japan in 1965, hundreds of Japanese cases have been documented, as have several in the United States (10). Up to 1990, more than 12,000 cases were reported from Japan and only 519 cases were reported in 19 countries outside of Japan, including Spain, France, the Netherlands, and Germany. Approximately 3,000 individuals suffer from Anisakis each year in Japan. The majority of these cases involve gastric anisakiasis, and colonic anisakiasis is extremely rare. Less than 100 cases have been reported from the United States; however, this infection is probably misdiagnosed and underreported. During the past 2 decades, there has been increased documentation of cases of infection from New Zealand, Canada, Brazil, Chile, and Egypt. With the tremendous increase in the popularity of sushi and sashimi, it is likely that the number of case reports will continue to increase over the next few years. It is well recognized that human infection can occur from the ingestion of raw or poorly cooked marine fish or squid. In one fish market in Japan, 98% of the mackerel and 94% of the cod were infected. Pseudoterranovosis rarely occurs in Japan and Europe. However, it occurs more frequently in the United States and Canada, where P. decipiens is mainly transmitted by the Atlantic or Pacific cod, Pacific halibut, and red snapper.

Anisakid larvae known to cause human infections include Anisakis simplex, A. physeteris, A. pegreffi, Pseudoterranova decipiens, Contracaecum osculatum, Hysterothylacium aduncum, Porrocaecum reticulatum, andThynnascaris spp. Within this group, A. simplex and P. decipiens are considered the most important human parasites. The term anisakiasis refers to infections with the genus Anisakis, anisakidosis refers to infections with members of the family Anisakidae, and pseudoterranovosis refers to infections with the genus Pseudoterranova.

(Upper Left) Anisakis simplex in cod; (Upper Right) Pseudoterranova decipiens in cod (Courtesy of Dt. Stig Mellergaard). (Lower Left) Anisakis in fish flesh, (Lower Right) Larval nematodes in fish viscera. (From A Pictorial Presentation of Parasites: A cooperative collection prepared and/or edited by H. Zaiman. Photograph courtesy of L. A. Jensen.)

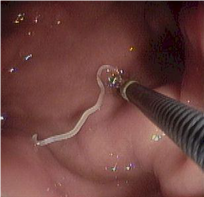

Right, example of colonic anisakiasis, a live worm (Anisakis simplex) found on biopsy of a large submucosal poly [in the descending colon of patient with abdominal pain and nausea; Left, Anisakis sp. being removed from the digestive tract.

Life Cycle:

The primary hosts of Anisakis are dolphin, porpoise, and whale; those of Pseudoterranova are seal, fur seal, walrus, and sea lion. These sea mammals ingest third-stage larvae, which penetrate the gastric mucosa and develop into adult male and female worms. The worms live in clusters, with their anterior ends embedded in the gastric wall. Eggs are then passed out into the sea, where the second-stage larvae are ingested by small marine crustacea (krill) and develop into third-stage larvae. These are then transmitted from krill to fish or from fish to fish, etc., via the normal food chain. The third stage larvae migrate into the viscera and peritoneal cavity. However, migration into the fish musculature may depend on environmental conditions and/or the species of parasite and fish. They are often transferred from fish to fish along the food chain, and as a result, some fish may amass large numbers of larvae. More than 150 species of fish can serve as intermediate hosts. Herring, salmon, mackerel, cod, and squid tend to transmit Anisakis infection, while cod, halibut, flatfish, greenling, and red snapper can transmit Pseudoterranova.

Acquired:

Human infection is acquired by the ingestion of raw, pickled, salted, or smoked saltwater fish or squid. The larvae often penetrate into the walls of the digestive tract (frequently the stomach), where they become embedded in eosinophilic granulomas. Occasionally, the throat is involved. These large larvae (third stage) measure 1 to 3 cm long or more by 1 mm wide. Histologic sections are characterized by the large body size, moderately thick cuticle, and large lateral cords that extend into the body cavity.

Epidemiology:

Although the distribution of anisakid larvae in infected marine fish is worldwide, within the United States salmon and Pacific rockfish (red snapper) are implicated most often in transmission. Although Anisakis normally has a marine life cycle, A. simplex and other anisakid parasites have been found in populations of river otter in the Pacific Northwest. This has been linked to the ingestion of shad during their spawning runs and outmigration. Thus, consumption of shad that are infected with anisakid worms may be confirmed as an emerging parasitic disease of veterinary and human medical concern.

Clinical Features:

The clinical manifestations of anisakiasis are varied, depending on the site of penetration of the larvae. There may be acute gastric presentation, which is the most commonly recognized clinical syndrome. Untreated gastric disease may produce chronic, ulcer-like symptoms and can be more difficult to diagnose. Intestinal anisakiasis is also seen, sometimes with acute symptoms and sometimes with a mild, chronic presentation; intestinal disease develops within 2 days after infection and occurs most often in the ileal region. Occasionally ectopic disease occurs, where the larvae are found outside of their usual location, usually elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract. Within North America, one of the most common presentations has been described as the “tingling-throat syndrome” and is often associated with infection by Pseudoterranova larvae. In these cases, the patient may even feel the worm in the oropharynx or proximal esophagus. The patient often coughs up the worm, which is then submitted to the laboratory for identification. Larvae in other true ectopic sites are rare, with the abdominal cavity being the most common; mild symptoms are usually the case, and the larvae may be found at surgery for totally unrelated causes. Apparently P. decipiens tends to be less invasive than A. simplex and is usually expelled by vomiting. A. simplex larvae tend to penetrate the gastrointestinal wall, invading the abdominal cavity.

It is well known that A. simplex can cause allergic reactions in sensitized patients. At present, a nonseafood diet is recommended for any patients with any kind of A. simplex allergy. Symptoms range from urticaria and isolated angioedema to anaphylaxis, and gastrointestinal symptoms can also occur. However, it appears that patients can tolerate the ingestion of seafood when the parasites are dead and noninfective.

There may be nausea or vomiting, often within 24 h after ingestion of raw marine fish. Depending on the location of the larvae, infections can mimic gastric or duodenal ulcer, carcinoma, appendicitis, or other conditions requiring surgery. There is usually a low-grade eosinophilia (10% or less) and a positive result for occult blood in the stool. Cases of pulmonary anisakiasis have also been reported.

Clinical Specimen:

The nematode larvae can be identified when submitted to the laboratory.

Laboratory Diagnosis:

A presumptive diagnosis can be made on the basis of the patient’s food history. Definitive identification is based on larval recovery or histologic examination of infected tissue. Although serologic reagents have been developed, they are not commercially available. Molecular biology-based methods may also provide some additional diagnostic tools. A rise in the levels of total and specific IgE in the first month after an allergic reaction, consistent with the patient’s history of gastroallergic anisakiasis, can provide valuable information, particularly if the parasite cannot be seen by fiber-optic gastroscopy.

Organism Description:

These large larvae (third stage) measure 1 to 3 cm long or more by 1 mm wide. Histologic sections are characterized by the large body size, moderately thick cuticle, and large lateral cords that extend into the body cavity.

Treatment:

There is no recommended therapy other than removal of the larvae, often through surgery. Gastric endoscopy is usually effective in larval location and removal. If the diagnosis is confirmed and there is no ileus, then surgical intervention can be avoided; the larvae will die and become absorbed within several weeks.

Control:

Raw, pickled, salted, or smoked marine fish should be avoided. All fish intended for raw, partly cooked, or marinated consumption should be blast-frozen to −35°C (−31°F) or below for 15 h or be normally frozen to −20°C (−4°F) or below for 7 days. This disease could be totally prevented by thorough cooking of all marine fish. Also, sushi served at professional sushi bars and restaurants is rarely responsible for infections. Generally in these settings, fish other than salmon, cod, mackerel, herring, whiting, and haddock are used for sushi preparation.